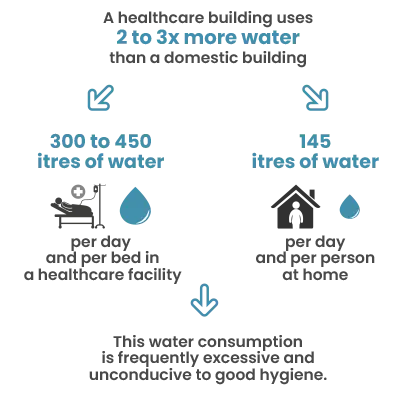

In hospitals and clinics, water consumption can reach 300 to 450 litres per day and per bed, in comparison with roughly 145 litres at home. This significant consumption is linked to multiple requirements: hand hygiene; sterilisation in operating theatres; patient hygiene, which takes more time and sometimes requires the intervention of nursing staff (showers); surface cleaning; laundry, and catering.

However, contrary to popular belief, consuming large amounts of water in these tasks does not necessarily improve hygiene: excess water can mask ineffective practices and does not prevent stagnation in the pipework. This creates an environment conducive to the development of bacteria such as Legionella, which can proliferate in just 72 hours.

Using less water to more effectively fight infection: a paradox

To limit contamination, standards and practices in many countries require flushing and draining of the system. Germany, for example, has the Trinkwasser (drinking water) standard, which requires points-of-use to be emptied after 72 hours of non-use. In other countries, taps are simply left open once a week for several minutes. However, in general, thermal shock at 70-80°C is recommended in the case of Legionella. This is an energy-intensive and complex process to carry out, depending on the condition of the networks. All these actions are carried out without specifically targeting areas of the network that are rarely used or contaminated, resulting in excessive water consumption.

Therefore, how can we address bacterial issues in healthcare facilities without wasting water?

Logical solutions: how innovation can reduce consumption

In practice, it is important to understand that the high water demand in a hospital is normal for the above-mentioned reasons. Showers, sinks, toilet flushes; it is, however, now possible to precisely adjust the amount of water delivered according to needs, thereby preventing waste whilst ensuring real health and safety.

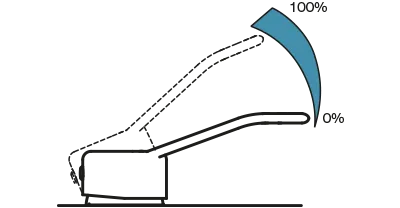

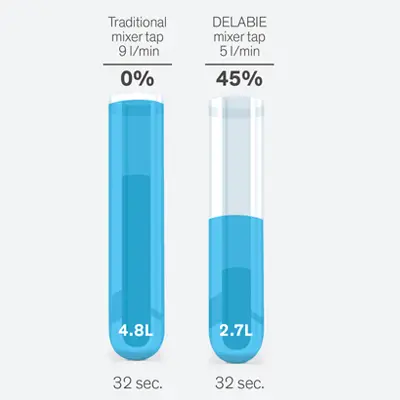

This is why French regulations (NF Medical) have reduced the flow rates of shower and basin taps. DELABIE shower mixers, capped at 9L/min (ref. 2739), incorporate flow regulators that maintain sufficient pressure for washing whilst preventing excess water consumption. The same logic applies to DELABIE basin mixers, which are generally regulated to a flow rate of 5L/min (ref. 2721T).

Sequential or thermostatic mixers taps (ref. H9614P) mix hot and cold water on demand, ensuring a stable temperature and thus reducing the amount of water wasted whilst adjusting the temperature. In addition to improving user comfort, they also reduce the energy consumption associated with hot water production, whilst helping to limit bacterial growth thanks to optimised flow rates.

For care staff handwashing protocols, electronic taps are now widely specified. A wall-mounted solution such as the TEMPOMATIC electronic wall-mounted tap (ref. 20804T2, for example), uses infrared technology to detect hands. Water does not begin to flow until the user approaches, and stops automatically when the user moves away, avoiding all unnecessary water usage.

Finally, flush systems can also be a large source of water wastage and bacterial proliferation. On the one hand, a cistern flush can present an increased risk of leaks (up to 200m3 of water wasted in a year), on the other hand, it is also synonymous with hygiene risks, as its water tank predominantly remains stagnant. To reduce the risk of these eventualities, a cistern-less flush system (ref. 763000, 464000/464006) offers itself as the best option, due to its reliable mechanism, without water stagnation.

Additionally, electronic water controls include a duty flush function, activating the flow of water every 24 hours after the last use. This optimised purge mechanism allows for the water in the system to be refreshed regularly, thus limiting bacterial proliferation, whilst avoiding excess consumption.

Organisation and maintenance: the hidden force behind water savings in hospitals

Outside of specialist equipment, proactive management of the water network plays a key role in saving water in a healthcare environment. In the first instance, it is essential to identify the points of use which could pose a sanitary risk, especially those which are used infrequently.

These areas thereby allow for water stagnation, leading in turn to bacterial development. Once these points have been identified, a both simple and long-term solution is to replace the existing water controls with a DELABIE electronic mixer, or to install one nearby.

At the same time, it is also essential to regularly check the water temperature (verifying that it is not between 25-45 °C, where legionella propagates); to detect and quickly repair leaks (a single drip per second can represent tens of litres lost every day), and to monitor biofilm via targeted sampling or inspections. By integrating these actions into a preventative maintenance plan, bacterial contamination risks can be reduced effectively, whilst avoiding systemic water wastage.

When water savings and hygiene align: working towards more sustainable hospitals

Saving water in hospitals does not mean compromising on hygiene. On the contrary, reducing unnecessary volumes limits stagnation and therefore the risk of bacterial growth. Heavy-duty interventions (thermal or chemical shocks) remain possible in cases of proven contamination, but every day use can be optimised. Above all, it is a question of consuming ‘better’, meeting medical needs and ensuring the safety of patients and staff, without abusing a resource that is as precious as it is costly.